Flying Fish

·«·« I »·»·

My heart pounds as seawater begins to envelop the cockpit. I breathe in the cabin's faint honey-suckle scent and adjust the four-point harness hugging me into the high-backed impact gel seat.

Initiating boot-up routines using the ship’s virtual control panel, I scan the status readouts glowing green across the ship’s head’s-up display. This aquila’s in good condition. I made sure of it.

“Buen día, Elara,” says Nereus over my implant, “Pre-launch sequence nearly complete.” My shoulders drop a few millimeters and a grin spreads across my lips as I hear the AI’s Texican accent.

Nereus’s voice is a mod I generated and uploaded two missions ago based on my uncle Larry … with his blessing of course. Today I’m reminded of the times he took me on long walks in the grasslands around his ranch outside of Houston. I remember an early morning when he paused us to watch a nine-banded armadillo saunter back to its burrow. His voice is good company.

“Morning, Nereus. Let's get this show on the road.”

“Alright, El. System’s all green. This fish is rarin’ for open water. Launch in ten, nine, eight …”

My mind drifts to last night. I probably had one or two too many mezcal margaritas going drink for drink with Angelina from the medical team, who I rarely see outside of the med bay. But it was worth it - her skin, normally as thick as an abalone shell, grew porous with the mezcal. She’d tasted like the peanuts we’d been munching on.

Adrenaline clears the last wisps of brain fog I entered the aquila with. The fog would have been much denser if my sleep chamber hadn’t run a few extra remediation cycles via my permanent IV port as I was falling asleep. I feel great.

“two, one …”

My body is pressed back into the cool gel as the underwater dock spits us out a tube and into the ocean like a torpedo. A gentle whooshing is all that makes it to my ears through the ship’s sound dampening.

“Sensors nominal,” says Nereus.

Acting as his ears, eyes and nose, the aquila’s optical, sonar, electromagnetic, chemical and thermal sensors allow Nereus to perceive the physical world around the ship.

A humanized version of what Nereus is sensing comes up on the ship’s heads-up display and the hull panels around me, giving the illusion that the aquila is almost completely transparent. Although it would be too dark for my unaided eyes, I’m able to see a group of coral formations below us teeming with life.

Glancing up, I watch the surface roll and distort as a morning storm sends fifteen foot waves crashing against the research rig’s illuminated pylons and elevator shafts. The rig has been my home for the past nine months, and its forty two inhabitants - my people.

I can barely tell when the aquila’s thrusters fire up to match our ejection velocity. They begin to propel our slim, six-meter-long ship farther out into the ocean.

“Updating our navigation models with new readings and charting our course,” says Nereus.

A map of the Pacific appears before me, a gently snaking line tracing our planned route to a series of ridges on the western edge of the Mid-Pacific Mountains, about 4000 kilometers due west of Hawaii. My mission is to investigate an unexplained disruption of marine migratory patterns there. Some mammals my team had been tracking were still stuck there after several days, seemingly unsure of where to go next.

“El, I reviewed the historic image data from Sativa, and I found the faint suggestion of three submarines in the target area 64 days ago, but nothing since, and not much before - it’s a pretty desolate patch of ocean. The silhouettes were faint and didn’t match anything in our database. I haven’t found surface matches for them elsewhere. They probably live in deep wet docks at their port of origin.”

Sativa is our real-time satellite imagery system used to catch illegal burning, dumping, harvesting and mining operations. Unfortunately even the most advanced satellite hardware can’t see much past fifty meters below the surface of the ocean - water is just too effective at absorbing and scattering energy waves. Still, the system allows us to find a wide range of superficial issues and helps Nereus keep tabs on everything above and just below the waves.

“Alright,” I say, “Give Sativa instructions to set up a watch on anything in the vicinity while we’re on route just in case anything comes up.”

While my mother was still alive, we’d both worked on the early stages of Sativa, although on separate pieces of it. She had been a machine vision optics expert and had developed some of the core technologies used for the second generation of fully autonomous terrestrial vehicles. Pieces of her still live in the system and I think of her when we use it.

·«·« II »·»·

“At cruising speed, El.”

I loosen my harness, lay my seat flat, and flick a switch that gently glides me back into the midsection of the aquila.

“Nereus, please put on my ambient playlist that starts with an old Tycho track.”

As the soothing synths, drums and guitars of “Into the Woods” begin playing, I survey the aquila’s onboard lab interface above my head. Our route is taking us through some relatively uncharted areas - an opportunity to fill in some of our knowledge gaps. I tell the lab to collect seawater samples every few minutes en route.

The lab will run realtime chemical, nutrient, and environmental DNA analyses, as well as monitor plankton and other microorganisms. I’m excited to sift through the data, see if there are any new creatures - maybe one of them will be voted as discovery of the month back on the rig. If it receives the honor, its likeness will be crafted into a pet-sized plush pillow by the rig’s fabricator. I’d like to add a fifth to the four back in my room.

Ever since my parents had taken me on my first dive to the Mesoamerican Reef off the coast of Cozumel, I had been enamored with the ocean and the multitudes of life it contains. I remember the awe I felt when I encountered my first trunkfish with its triangular body and perfect hexagonal paneling on its sides, the brilliant iridescent blues and oranges of a pair of coral shrimp posted sentry inside an azure vase sponge, and the massive elegant wings of the spotted eagle ray that swam past us.

By the end of the week in Cozumel, I had filled half a notebook with dive notes and scanned and identified 198 different species using a dive app. After I got home to San Francisco, I changed my concentration in school to marine biology and devoted myself to understanding, exploring and protecting life in the oceans. All four of my parents had been encouraging, with mama Mina trying to make sure I stayed in touch with terrestrial life by gifting me a tiny kitten named Jackie.

“El, there’s a large school of bluefin directly in our path, skirting it will take a couple minutes.”

An overlay appears on the lab interface in front of me, highlighting the enormous mass of fish ahead. The bluefin population had made a staggering comeback as simulation sushi became nearly as good as the real thing and at a tenth the price.

“Give ‘em a gentle honk,” I tell Nereus.

My younger self would have skirted around them, leaving them completely undisturbed. But now I don’t mind interacting with the animals as long as they’re mobile enough and I’m not forcing them onto a course with a predator.

“20 meters from the school, activating the sonar pulse emitter,” says Nereus.

Calibrated to create focused, low-frequency sound waves, the device sends a few dozen fish scattering ahead of us, making a clear passage for the aquila. I watch the shining scales and eyes of the passing fish on the interior paneling of the aquila. They remind me of some of the real and virtual field trips I had while studying marine biology.

After completing my PhD in Copenhagen, I worked my way up as a marine biologist to manage a team of researchers at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego. At the time, the acceleration of ocean acidification had been slowing as had the warming of the oceans thanks to transnational geoengineering projects, so our focus was on habitat restoration. My team and I were called to postings around the world to lead marine remediation and management projects.

After seven years at Scripps, I was invited to Hawaii to become one of the twelve governing members of a consortium of governmental and non-governmental organizations called the Conservation of Oceans and Reefs Action League (CORAL). The group exists because despite advances in climate solutions, marine ecosystems remain in danger from acute pollution, overfishing, and resource extraction.

In my capacity there, I’d proposed and founded a pilot program for a group devoted to investigating and intervening in unsolved issues in international waters. Thanks to CORAL’s considerable financial and political resources, we finished construction on the research rig just a year ago.

A link request alerts me on my implant - it’s from Subu.

“Elara, just wanna give you an update on our latest analysis of remote sensor data from the target zone - we detected some patterns in the magnetic disturbances that match the profile of some new mining equipment, Mythri Corp series CH87 … I’m sending you the very limited specs we’ve been able to scrape together … our systems had to scrub out a ton of noise that was obscuring the signal, but there it was, clear as day.”

“Thanks Subu,” I say, “makes sense with all the rich metal deposits in the oceanic crust on those ridges in the target zone.”

“Be careful,” says Subu before I cut the link”

Subu Chatri has been my main connection to the research rig, a highly skilled data and comms specialist. She has guided me on numerous missions, and I trust her completely.

“Nereus, can you summarize the data Subu just sent over and construct models of the machines based on it?”

“Sure thing. The series CH87 is the latest deep sea mining machine to come out of Mythri, a large indian megacorp. According to official records the series CH87 hasn’t been deployed anywhere yet. There isn’t much data available on it aside from its power requirements, crew capacity, and reported production capacity for polymetallic nodules and sulfide deposits on the order of tons per minute. Third party reports state that it uses some proprietary electromagnetic technology to break apart sediment and rocky crusts to then hoover up the precious nodules and deposits. Attached to the briefing is an electromagnetic wave recording file of what is supposedly a CH87 in the wild.

In recent years, covert illegal underwater mining operations had been responsible for destroying countless ranges of thousand-year-old deep-sea sponge and coral ecosystems. On top of that, the discharge plumes they create are as suffocating and toxic for sea creatures as a dense fire can be for terrestrial life.

I move my seat out of the ship’s midsection and back into the cockpit, returning to a seated position. Above us, the storm has mostly passed and cool morning light is beginning to filter down from the surface.

·«·« III »·»·

“I found some promising conveyor currents and updrafts,” says Nereus, “remnants of that storm. Should carry us pretty far in glide mode, my estimates give us 1000+ kilometers. That’ll gain us some time, save us a couple units of energy and even gain us a unit from the sun.”

“Perfect, let’s jump.”

The aquila angles upward and begins to accelerate towards the surface.

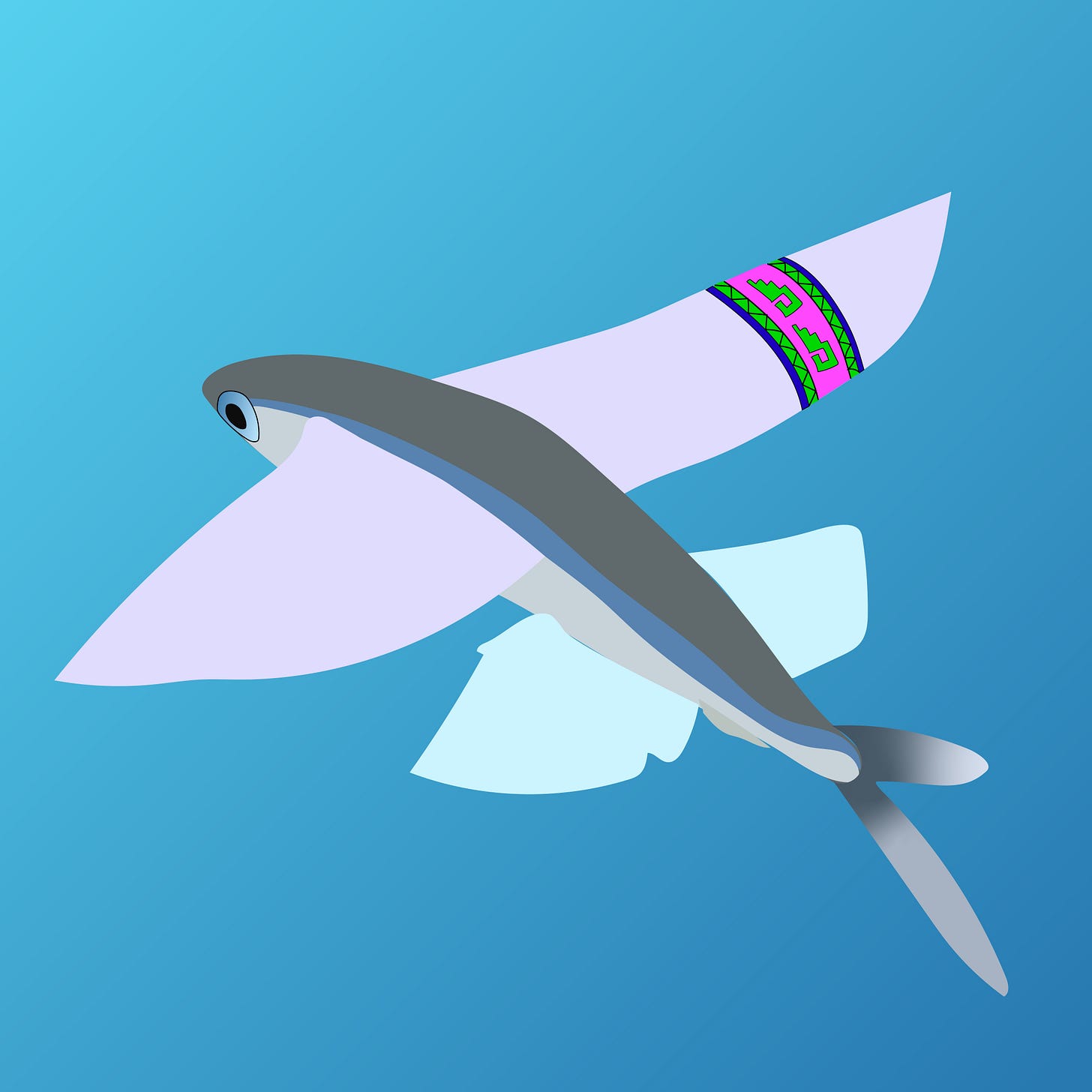

Two sets of long, several-millimeter thin wings spring from the sides of the aquila as it breaks the surface and leaps from the crest of a wave. The ship’s wings catch an updraft and the Nereus stabilizes the ship in a matter of seconds.

“Jump successful. We’re gliding like a cottonwood seed on a summer breeze,” says Nereus, “Let me know if you want the controls.”.

Modeled on the Atlantic flying fish, the aquila’s design had been my brainchild almost a decade ago. The larger front pectoral fins and the smaller rear pelvic fins act as airfoils that enable long-distance gliding using updrafts and wind currents close to the ocean’s surface.

I’d been mesmerized by the flying fish on a high school trip to Catalina island off the coast of Los Angeles. Afterwards, the metamorphosing creatures appeared in my dreams often, along with hummingbirds, well into my 20s.

The aquila’s display shows that we’re traveling over the water at just under 140 km/h or 90 mph. A good clip, considering we’re not burning any energy.

I’d worked many late nights with Hussein, an engineer at the lab I’d been working at when I’d thought up the aquila, before applying for a grant for the ship’s development. The first version came out three years later. I’m flying the latest version, 4.3.17, 4 indicating the major hardware revision, 3 the minor hardware revision, and 17 the software revision.

I watch the sun rising behind us begin to paint the western horizon with strokes of orange and purple. Our semi-opaque wings, holding cells capable of harvesting solar energy, begin to register a faint current. The solar wings have come in handy on a couple missions where I’ve run out of energy, allowing me to gain enough charge over the course of a few days to get home.

Somewhere between aquila version 2.0 and 2.3, the navy caught wind of the project and started developing its own version that could evade torpedoes and missiles by either flying or diving and was equipped with offensive weaponry. While I didn’t like this turn, I had used similar evasive tactics once to avoid an automated torpedo launch after getting a little too close to a military installation off the coast of morocco. And the navy had agreed to keep them apprised of the latest tech they were applying to their lineage, with a lag of about 2.5 years for security reasons - meaning the aquila had gotten some pretty sweet upgrades over the years.

I watch on the display as the aquila extends a thin retractable arm down into the water to collect seawater. We’d built that functionality into flight mode in version 3.0 for the lab, complete with a programmable sampling rate.

Nereus, named after the Greek god of the ocean’s bounty, had been built by our data science and AI team after version 1.7. The original AI system had been trained on decades of underwater navigation and operational data as well as autonomous glider and flying drone data. I still contribute occasional software patches and tweak the model’s parameters.

I don't realize the sun has fully risen until I glance out the window - Nereus has been modulating the ship’s window tinting to maintain a constant brightness. Wispy white clouds dot the southern horizon like cotton balls ripped apart and thrown on a brilliant blue canvas. One of the clouds is vaguely cat-shaped and reminds me of Porcini, my large tabby I’d nicknamed Porky. Porky is probably curled up on his favorite plush pillow, an amoeba-like hastigerina pelagica, back in my cabin on the rig’s habitation deck.

Too early to think about home.

As if in agreement, Nereus pings me to tell me we’re passing close to one of CORAL’s autonomous solar-powered remote sensing units, a submarine-like vessel the size of a dolphin.

“The remote just beamed us a packet of encrypted data - looks like recent local seawater and climate observations. Nothing juicy but I'll integrate some of it into our own data collection,” says Nereus.

“Great. Nereus, I’m ready to take the controls. Make any flight path recommendations to keep us aloft as you see fit. Oh, and change the playlist to the Guardian’s of the Galaxy Part I on shuffle. Thanks.”

As the punchy guitar and drums drive into the opening lines of “Cherry Bomb”, a flight yoke extends from an aperture in the dashboard in front of me. Nereus adjusts its position so that it comes to rest about a foot and a half from my sternum.

“Releasing flight controls to you in three … two … one”,

The aquila responds gracefully to my touch, dipping and rising over the waves, dancing with the sea breezes. Gliding in the aquila feels like surfing the ocean’s salty breath.

I bank considerably more compared to Nereus’ efficiency-minded flying, but that’s what makes it fun. And it’s a much smoother roller coaster compared to the flying lessons my ex gave me in an old prop plane outside of Copenhagen.

“El, I see an albatross to your 2 o’clock, about 500 meters away.”

I spot the bird and tilt the yolk slightly to the right to bring us closer.

“Nereus, scan it when you can. It’ll be good to catalog what condition it’s in and where it’s heading.”

One of the most efficient glider’s on the planet, the albatross inspired pieces of the aquila’s flight mode design. I watch its impressive ten foot wingspan skimming over the water and silently thank it for its teachings. I can’t afford to slow down and have the aquila match its 110 km/h, so I turn back to the left and reestablish our original heading.

“Nereus, lay out a training course ahead of us, level 7.”

On the display, rings and stars of various colors appear above the water. I angle towards the first ring and narrowly pass through it to collect the two stars on the other side.

After half an hour of flying, I rack up 105 stars and am beginning to lose focus. I release the controls back to Nereus.

I think about Erik, one of the aquila pilots I often train with back on the rig. He would have enjoyed this assignment, his specialty being migratory disruptions. But he took a mission just a few days ago and is still out surveying reports of a disturbance off the coast of Portugal.

Flying gives me an appetite. I open the refrigerated drawer and grab one of my meal packs with lettuce leaf and a fish emojis on it. Inside is a fresh salad of green and red leafy greens, seaweed, and cherry tomatoes, alongside a delicate filet of white fish, complemented by a drizzle of tangy citrus dressing. All of it is grown in the research rig’s automated aquaponics system. The meal prep robots back on the rig really do a wonderful job, even with to-go meals. The marine-degradable container is basically fish food.

An incoming link on my implant.

“Hey Ari,” I say through a mouthful of lettuce, “what’s up?”

“Elara,” the dock manager’s gravelly voice responds, “just wanted you to know I equipped your aquila with an upgraded ink cartridge … We got the new formula from the folks over in the Caribbean who swear by it - basically, the ink particles also contain biodegradable polymers and composites that’ll confuse acoustic sensor systems. And the ink’ll cling to anything metal, plastic or glass that tries to pass through, so any aggressor will be pretty hosed unless they’ve got the most advanced windshield wiper system on the planet.”

“Cool, thanks Ari,” I say, “Hopefully I don't need to use it.”

I close the link.

·«·« IV »·»·

“El, the sea is calming down and I can't find a route forward that would keep us aloft, so we’ll need to re-entering the water in a couple minutes,” says Nereus.

We went 1,172 kilometers flying on updrafts and air currents. No record there, not even close to Richard’s 1,933 kilometers glide off the coast of Chile where he’d captured just over two units of solar. But he’d let Nereus do all the flying - no fun.

Dipping the aquila’s nose ever so gently, Nereus optimizes our approach for minimal impact, angling the ship’s wings slightly to slow us to under 50 km/h. My harness tightens a notch. We touch the water and I feel a light jolt as the cabin’s suspension system absorbs the rest of the shock. In moments the aquila is fully submerged and the thrusters begin to push us through the water.

“Nereus, turn on our active cloaking,” I say.

I hear a slight whine while the system comes online.

“Done. We’re gliding through these waters quieter than a gopher snake through a library,” says Nereus.

“Nereus, remind me to tune the parameters for your Texican vernacular.”

He shows me a saved reminder on the display, but doesn’t respond.

As we approach the target coordinates, the aquila's magnetometer begins to pick up the anomalous electromagnetic readings matching the recording in the mission briefing.

I open a link to Subu.

“Hey Subu, I'm about to go down deep. I’ll post a comms buoy and stream all the Aquila’s sensor data through it to you and the rig.”

Per my instructions, the aquila pops out a comms buoy the size of a basketball from a rear hatch and it floats to the surface.

“Alright, I've got a lock on your buoy and the data stream should start in a moment. Our connection is now using that buoy as a relay. Open a link whenever you need it”

“Thanks Subu. All good on the rig?”

“Yeah, all peachy here. Erik says the Portuguese coast guard is giving him hell even though the target zone is right outside their jurisdiction and is affecting their fishing fleets.”

“Well, not the first time a government has wanted to do its own sleuthing and keep everyone else out.”

“Truth. Alright, be on your guard down there,” says Subu before she cuts the link.

“Alright …Nereus please drop us down to within 1200 meters of the epicenter of the electromagnetic disturbances.”

As we venture deeper, a strange ballet of disarray unfolds on the screens around me. Species of marine life, usually never seen together, swim in confused patterns. A pod of dolphins darts past, their sonar clicks rapid and disoriented. Nearby, a group of sea turtles, who should have been hundreds of kilometers away already in their nesting grounds, paddle aimlessly. Schools of fish swim in tight, confused circles. A lone shark, its migratory path disrupted, veers close to the aquila, its eyes flicking back and forth as if searching for a familiar landmark.

My cheeks flush, and a heat rises in my chest while a small knot begins to form in the pit of my stomach. I feel a deep sense of anger as I remember the first time I saw some divers molesting the inhabitants of a coral formation. They had been poking their gloved hands into crevices and breaking pieces of coral in the process - I’d wanted to stop them but didn’t want to endanger myself or any of them at 30 meters down, so I took a video of them instead, hoping to bring them to justice back on land.

“El, we're 1200 meters from the target. I can’t see much - our sensors are unable to penetrate the dense cloud of silt and sediment surrounding the target area.”

On the ship’s displays, I watch as Nereus tries to blend data to bring more detail and definition to the large blob below us.

“From what I can tell,” says Nereus, “the cloud is around 1 kilometers thick and several kilometers long, and thinner on the eastern edge due to a gentle current, thin enough that our passive sonar can just make out a man-made object.”

The image on the screen zooms in, and the form of a massive machine comes into view. It reminds me of a terrestrial pile driver, only 10x larger and with six stabilizer feet instead of treads. I stare at it.

“You seeing all this, Subu?”

“Sure am. Definitely looks like our CH87.”

“Damn. All these poor creatures. I'm gonna get a closer look.”

I send a set of commands to Nereus to deploy a small, remote controlled drone called a barracuda. Its body is long and narrow like its namesake, about 4 feet long and a foot round. It and all of its components were designed by the navy so it has top grade electromagnetic shielding and state-of-the-art stealth technology. I use its virtual control panel to guide the drone towards the semi-exposed machine. It slips through the water undetected.

As the barracuda approaches the mining operation, its passive sonar sensors, relayed through Nereus onto the aquila’s screens, reveal a staggering scene through the silt. Fifteen of the machines cluster together, their feet dug into the sides of the deep sea ridge, wide-bore ram tubes sticking up 20 meters above them. The barracuda detects massive electromagnetic wave pulses just before each ram strike. The ram impacts burrow deep into the ridges and blow the crust asunder. Tentacle-like tubes suck up larger chunks of crust while the rest drifts away to join the cloud of sediment.

I target the easternmost semi-exposed machine.

“Nereus, help identify the control pod on the machine based on the data stream”

“Affirmative, it appears to be situated on the top, on the side opposite the ram tube.”

I instruct the barracuda to release its own microdrone, about the size of my hand, and for the microdrone to attach itself to the control pod.

Swimming closer, the microdrone scans the machine for identifiers but finds none. It does report that many of the external components match those in the database of Mythri corp parts. Once attached to the pod, it scans for any comms, data channels, or acoustics and begins streaming an upsampled rendition of one half of a conversation happening inside.

“Ram six is getting real hot … tell Rina to give it a break for about thirty mins and run an inspection … I’m at 31.6 tons per hour and decelerating by about 8% an hour … ok, we’ll probably need to move down the ridge in about six hours … yeah, I heard the next pickup is in three hours? … my hamper is about 70% full … hq says the crust is prime, plenty platinum, silver, gold and tungsten? Wish we could keep a little of the shiny stuff to ourselves…”

While the audio stream continues, I issue commands to the barracuda to autonomously recon the other machines as best it can through the silt and sediment cloud.

“Subu, do we have any friendly assets within three hours of here?”

“Let me check.”

A new link alert comes in on my implant, this time from Yana. She’s another governing member of CORAL, but chooses to stay on land, mostly working on strategy, policy and finance.

“Elara, I just got an alert from your mission resource group. Sounds like you’re asking for backup. I think it’d be wise to hold tight and wait for reinforcements.”

I’m already annoyed.

“Backup would be nice, but I’m fine on my own, Yana. I don’t want to miss this opportunity to track their ore mule.”

Ore mule is our name for a covert cargo sub that carries away illegally mined ores from deep sea operations.

“I get that, Elera, so why don’t you just wait to tag the mule and then get yourself home?”

She can’t see me shaking my head in frustration. This always happens when people are so far removed from the action. They forget. It’s a slim chance, but I’ll see if I can get her to come on one of these missions in the future.

Some heat rises in my voice and I let it through.

“Do you see the scale of this? Every second we wait, thousands of creatures are being crushed, smothered, or otherwise annihilated down there. Not to mention all these migratory fish and mammals who are probably starving and terrified.”

“You don’t have the equipment to take on all those mining machines. And who knows that they’ve got down there working security.”

“Well, we’ll figure something out. We have before. I can’t just leave this alone, Yana.”

“Ok. I can’t stop you. But you know we can’t afford to lose you or that ship. Please use the utmost caution.”

·«·« V »·»·

I take stock of the offensive devices onboard the aquila - there’s our bow harpoon and the remote electromagnetic pulse (EMP) devices. The EMPs are designed to disable electronic equipment in a targeted area. I know these mining machines will be EMP hardened, given the electromagnetic ramming technology they are using. Maybe an EMP directly on the side of each machine’s control pod would be strong enough. But I only have two, so that isn’t going to work.

“Negative on the friendlies,” says Subu.

“Shoot. Ok Subu, so the barracuda’s microdrone is looking for some paths into their system.”

“I'm getting the data stream,” says Subu, “looks like they’ve got some good network hardening and defenses. There are potentially some channels we could take advantage of, especially around their acoustic command system. It’s a small attack surface, but could do the job.”

“Nereus, what’s your read?” I ask.

“I just analyzed the barracuda’s sensor data from the other machines - we’ve got something interesting,” says Nereus.

On the aquila’s main display, Nereus highlights a machine near the middle of the cluster.

“That mining machine is sending encrypted acoustic commands to all the others,” says nereus. “Based on initial probing, it might take me six hours to crack the encryption.”

I consider this. I want to deal with this well before the ore mule’s pickup window.

“Subu. big ask - can you commandeer as much of the research rig’s processing power as possible to help nereus decrypt these commands? The barracuda and microdrone will continue to collect acoustic emissions as well as any other signals.”

The rig’s A.I. system, Kiwa, which our team named after the Maori guardian of the ocean, has about 50x the compute power of Nereus.

“Shouldn’t be a problem, it's mostly quiet around here. Looks like I can allocate 85% of Kiwa’s processing power.”

“Thanks. Nereus and Kiwa should be able to handle this together.”

“Nereus, open a compute collab channel with Kiwa. I want you to both work on decrypting the acoustic commands, reverse engineering the command protocols, spoofing the command authenticity, and then crafting an emergency shutdown and evacuation command.”

“Got it. Kiwa and I are linked, starting to decrypt those commands.”

I open a drawer to the right of the pilot’s seat and pull out an energy bar to snack on. Missing Porky, I pull up an old classic game called Stray III on a side display. In it, I explore an open-world dystopian city as a cat with various jumping, climbing, and stealth skills.

The audio stream from the mining machine continues, mostly banter and some long silences. The aquila highlights several objects drifting downward - dead fish who had likely starved in the disoriented chaos above.

After fifty five minutes, Kiwa and Nereus have deciphered the commands and compiled a comprehensive set of command patterns.

“Based on their command palette, we developed three candidate emergency shutdown and evac commands complete with authentication,” says nereus, “then we ran them in tens of millions of tests against simulations of the CH87’s systems, and feel confident in the top scoring one.”

“Woohoo!” says Subu, “After we issue the command, the central CH87 will still be online - how’re we going to deal with it?”

“Nereus, what are our options?”

“The barracuda’s microdrone has been conducting various tests on the skin of the CH87 - the control pod in particular - to analyze its composition and inner structure. I’ve already run the simulations with Kiwa and we have a 54% confidence rate that an EMP could disable the main machine.”

“Not good enough. How about two?”

“If we can afford two, reprogram them slightly, and position them properly, it will be possible to achieve a superposition of the two - their electromagnetic waves overlapping and combining to form a new, more powerful wave pattern. Give me a second while I run some sims with Kiwa…”

“Ok, in a dual configuration, our estimate is now up to 87% chance of success.”

“I’ll take it. Would we endanger the life of the operator?”

“No, unless they have a life-critical medical implant that’s susceptible, but I doubt they’d hire anyone with such a condition for this work. The pressurization will hold and there should be plenty of oxygen and embedded chemical lighting for them to get to their escape pod and release it manually.”

“Ok, let’s do it.”

I instruct the barracuda to return, pick up both EMPs with its two robotic claws, then head back to the central mining machine to precisely position them according to Nereus’s waypoints.

“The EMPs are in position,” reports Neureus, “I’m having the barracuda align itself to issue the shutdown and evac commands.”

·«·« VI »·»·

Tiny blue and red emergency lights begin to blink furiously on the display in front of me.

That’s not good.

“Elara, we’re going to need to take evasive action,” says Nereus, “A piranha class security drone has our scent. Didn’t get a reading on it until just now - they’re sneakier than a mama coyote slippin’ through switchgrass.”

The heads up display highlights an object approaching us from the south, shaped like a chonky torpedo that’s twice as tall as it is wide.

“It's scanning us,” says Nereus.

“Tell it our compass is malfunctioning and we’re lost?” I suggest, only half joking.

“It’s refusing any comms connections. Targeting us now. Targeting locked.”

“Full speed into an evasive maneuver, Nereus. We collected enough sun today to burn the thrusters a little extra hot.”

The weight of the acceleration presses down on my chest as the aquila corkscrews up.

“Torpedo launch detected, twenty seconds to impact,” says Nereus, “deploy decoys?”

“How much ink do we have?”

“Three full or six mini squirts. Mini should be sufficient for the torpedo.”

“Let’s try our decoys first, and if that fails let’s use the minis.”

“Decoys away … impact in 14 seconds, 13 seconds, 12 seconds … torpedo not changing course, impact in 11 seconds. Deploying ink.”

I remember the first time I witnessed a small Caribbean reef squid release its ink to evade a reef shark that had been harassing it. The dark cloud had thoroughly confused the shark for a few seconds, enough time for the squid to scoot into the safety of a crevice in the coral.

I feel a faint shudder from the aquila and watch the ink through the rear displays, a growing cloud that quickly veils the inbound torpedo.

I take a small sip of air and hold it in. All I can hear is my heart thumping.

“Looks like … ” says Nereus, “ … it dodged”

I watch on the display as the nose of the torpedo emerges around the edge of the ink cloud.

“Its maneuver bought us some time though. Now that I have more data on its capabilities, I can deploy the ink when it won’t be able to escape. 15 seconds to impact.”

“Coat the sucker,” I say.

Another faint shudder at 5 seconds to impact.

“It’s completely blind,“ says Nereus.

I watch the torpedo hurtle onwards in a straight line as we continue to turn. The cloud of ink behind us is still visible on the display.

“Can we hide behind the ink relative to the Piranha?” I ask.

“Yes, the ink cloud should be an effective barrier for another minute or so before it dissipates. Elara, we’ll lose our connection with the barracuda and the microdrone.”

“That’s ok. Let’s give this piranha a surprise.”

Nereus pilots and positions the aquila so that the ink sits perfectly between us and where he projects the security drone is now.

As soon as the drone comes around the edge of the ink and into our line of sight, the aquila springs out with a quick burst of its thrusters and we shoot a full payload of ink directly at it, coating it almost completely.

The piranha continues on its trajectory for a moment, bobbing slightly, then tries to reverse and throws itself off course. It spirals off into the blackness.

“The thing probably already reported most of this back to the mining machines,” I say, “let's re-approach quietly from a new bearing. Report to me as soon as you’ve reconnected to the barracuda and the microdrone.”

“Now that I have more data on these piranhas, I’ll be on a better lookout for any of that one’s comrades,” says Nereus as the aquila accelerates into a gentle, downward sloping arc.

·«·« VII »·»·

“Reestablished our connection to the barracuda. Tells me it’s still connected to the microdrone,” says Nereus, “It picked up an increase in acoustic communication activity among the miners during our dance with the piranha. The machines stopped ramming and lit up massive spotlights to help their optical sensors. Our barracuda is nimble and smart enough to dodge the lights, but who knows what else they’re going to try. I suggest we take action now.”

“Alright,” I say, “First the barracuda gets in place above the main mining machine and sends the commands, then high tails it out of there with the microdrone before we activate the EMPs.”

The barracuda’s sensor stream comes back online across the aquila’s displays - I see huge cylindrical beams of white light sweeping through the dark and crisscrossing, reminding me of a lightsaber fight from recent Star Wars remake.

“The barracuda is almost in position,” says Nereus, “Sequence starting in three, two, one … shutdown and evac commands sent.”

I think of all the struggling marine life and pray that our gambit works.

“Confirming command success - the barracuda isn’t picking up any acoustic comms anymore from the mining machines, and their strobe lights have been replaced by small red emergency flashers. Only the central machine is still strobing and attempting to send out communications and commands.”

“I’m doing some last millisecond tuning on the two EMPs to ensure a superposition of waves … and activating them now directly on top of the control pod,” says Nereus.

I see a glow on the hud and watch the magnetometer track the residual electromagnetic waves as they spread and fade. By now the current has cleared much of the silt and sediment around the machines, giving us a better view with our other sensors.

“No lights, no comms, that last machine is dead in the water,” reports Nereus.

“Yeehaw! We got ‘em. Thanks team,” I say.

“Subu can you notify CORAL that they’ll need to pick up some escape capsules around my coordinates asap? We’ll also need a surface ship and several submersibles to perform clean up. Hopefully between the operators and the data we’ve gathered, we’ll be able to figure out who was behind this.“

“On it,” says Subu.

“Nereus, recall the barracuda to the aquila so it and the microdrone can fast charge.”

“Of course,” says Nereus, “El, I’m starting to pick up some acoustic activity from the mining machines, probably the locking mechanisms that release their emergency surfacing capsules.”

I watch on the aquila’s displays as a small life capsule detaches just behind the control pod on one of the mining machines. More and more capsules start popping off their machines and drifting upward in a series of lazy ascents. The central machine’s escape capsule is dark aside from some chemical lighting strips on its skin, any circuits having been fried by the EMP. The other pods are studded with bright LEDs.

“Team,” I say, “keep your ears and eyes out for that ore mule that’s due in about ten minutes. And for any other piranhas.”

As the aquila rises from the darkness of the deep sea and into the sunlight zone, a wave of warmth and relief washes over me - the aquila’s monitors show very little macro biological activity. I hope those creatures find enough food along their routes to reach their original migration destinations.

“Nereus, send a message to Erik about freeing up all these marine friends - he could probably use some good news.”

“Sent with video evidence,” says Nereus.

“Alright,” says Subu, “a CORAL ship’s on the way.”

CORAL will handle the rescue and begin ecosystem remediation on the submarine ridges. They’ll work with the authorities from the operator’s home countries as well as with the California-Pacific Consortium. Some chance those operators are sworn to secrecy, but we’ll see how much information they’re willing to divulge to reduce their sentences.

“Eyes on the ore mule,” says Nereus, “It has decent stealth, but it’s a little leaky. Coming from the southwest, about 2.5 kilometers away. It’s an older model, a decommissioned nuclear, likely retrofitted. Unclear if they have surface rescue capabilities.”

“Ok, launch the barracuda toward it and let me know if anything changes,” I say, sliding back into the belly of the aquila, “I’m going to program the lab to collect some additional seawater samples here to better understand the effects of these sustained electromagnetic pulses on the microorganisms.”

I’m so curious I have the lab take a sample immediately and begin to analyze it. As I feared, all the magnetotactic bacteria, who contain magnetic crystals used for guidance, are dead. I’m not sure what effect that’s having on the rest of the food chain, but it’s probably not good. I program the lab to do a comparative analysis with the collections we took on the way here to understand more.

“El, the sub is slowing,” says Nereus, “coming to a halt about 2 kilometers away. They know something is amiss with the mining operation … they’re turning … now powering away.”

The barracuda’s microdrone is already discreetly attached to the sub’s side like a pleco sucker fish, broadcasting its position.

After re-absorbing the barracuda, we surface to pick up our comms buoy. I count fifteen escape capsules bobbing on the surface, their shiny domes reflecting the pink hues of the sunset.

“Subu, we’re coming home.”

“Copy that. See you soon, Elara.”